‘Kids in resi want love and to feel welcomed. Not like you’re in the gutter just because you’re in resi because your family has issues. Kids are going through hard stuff and if they act badly, they’re doing it for a reason.’ - Mia

The state provides residential care for children who can no longer live with their family when other out-of-home care (OOHC) options like foster, permanent or kinship care (living with relatives) are not available.

Children placed in residential care are some of the most marginalised in the community.

Many have been exposed to multiple traumas from a young age, including physical or sexual abuse, neglect or family violence.

Exposure to trauma often results in kids displaying challenging behaviour. This should be managed with an intensive, therapeutic care response. But all too often, residential care facilities resort to calling police instead. This includes for actions like breaking a cup or other property damage that wouldn’t attract a police response if it happened in a family home.

This over-reliance on police means the children most in need of help are pushed into a cycle of involvement with the criminal justice system, which often has lifelong impacts.

Since 2016, informed by our clients’ experience, we have called on the state government to adopt a new approach that focuses on providing a therapeutic response, not a justice response.

Because every child in residential care needs care not custody.

Latest news

Towards a better system

Providing care, not custody

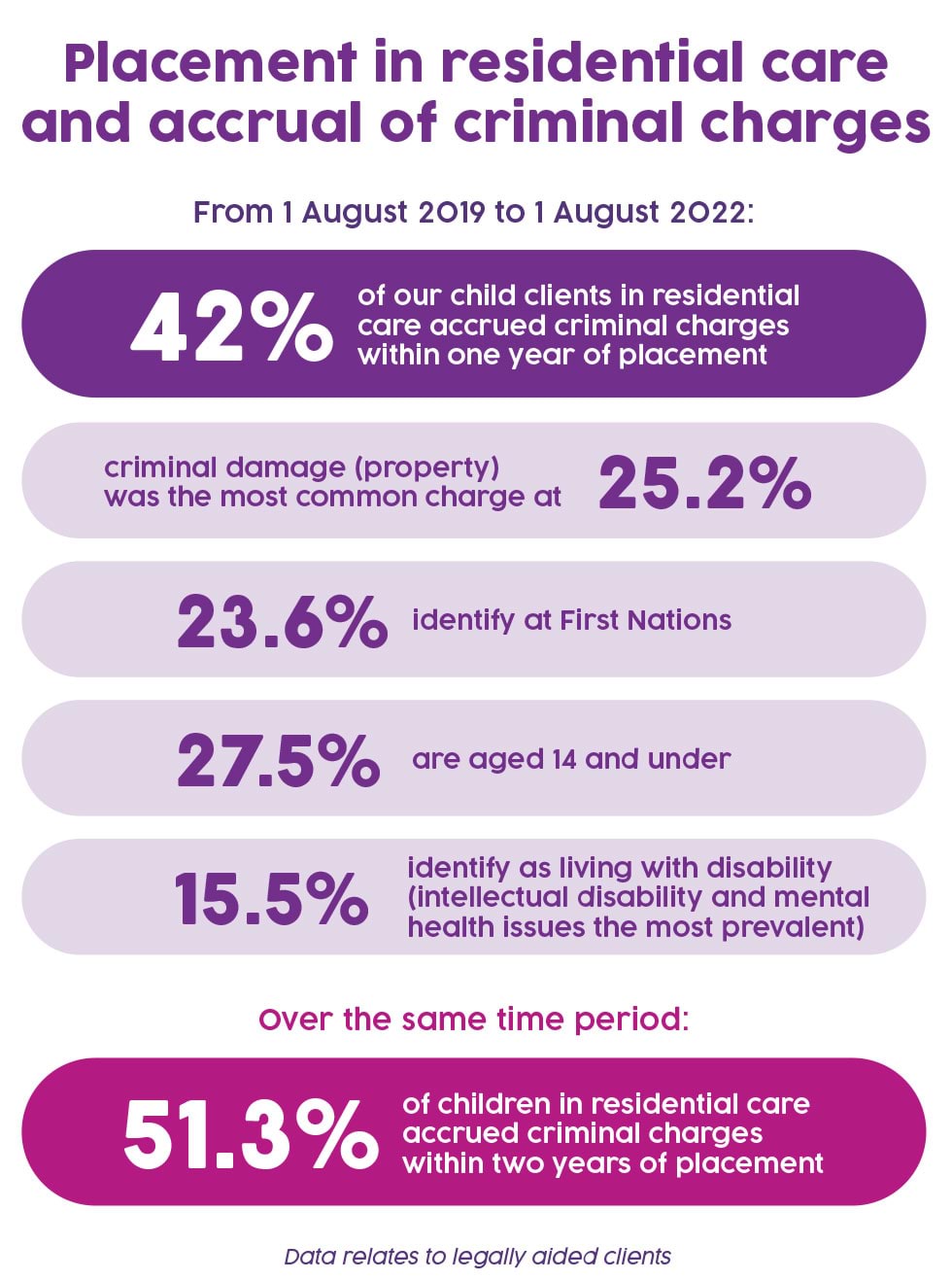

An analysis of our client data from August 2019 to August 2022 illustrates the high rates of criminalisation for children in residential care.

The data shows that two out of every five child clients living in residential care at the time of their final child protection order were involved in the criminal justice system within 12 months.

Within two years, every second child was charged.

The analysis shows that children in other OOHC environments are also more likely to face criminal charges than those living at home, but the highest rates of criminalisation occur for those placed into residential care settings.

A framework that lives up to its name

In February 2020, we welcomed the government’s introduction of a framework to reduce the criminalisation of young people in residential care.

The agreement between the residential care service sector, Victoria Police and key government agencies highlights the importance of trauma-informed approaches when working with young people.

It provides decision-making guidance for residential care workers so they can avoid calling police for low-level incidents. Crucially, it also states that charges won’t be pursued when there are viable alternatives.

But four years on, there is insufficient reporting to tell us if and how the framework is having an impact. While there have been some improvements, at court our lawyers regularly find police don’t know about the framework.

We continue to call on the statement government to formally take action to:

- ensure any relevant new policies and practices appropriately reflect the framework

- integrate the framework as an essential part of staff training across the sector and Victoria Police

- establish clear and consistent processes for escalating cases where the framework has not been applied

- establish better data collection and reporting to monitor the impact of the framework.

Raise the age of criminal responsibility

The over-criminalisation and over-policing of young children in care is one reason we support immediately raising the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14.

Read more about how making this change will better support children to thrive.

Our clients' experiences

More information

Read the full 2016 Care not custody report which includes additional stories from our clients.

Read the 2018 Care not Custody fact sheet with a data analysis of our child protection clients.

Read the Framework to reduce the criminalisation of children in residential care.

Updated