Intervention orders are rising against children and young people, but they often don't change children's behaviour or leave families and the community feeling safer.

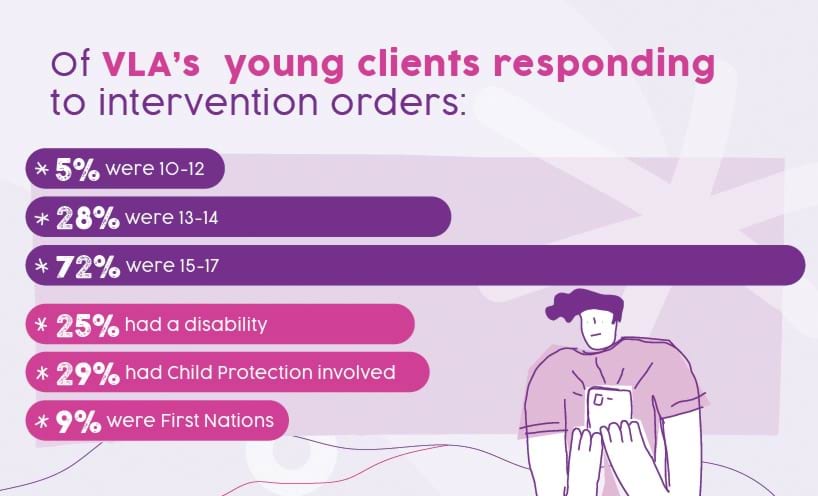

We represent thousands of children and young people who are responding to intervention orders. We have looked into internal and external data for the past six years and we've spoken with children about their experiences as child respondents to family violence and personal safety intervention orders around Victoria.

Children deserve every opportunity to grow up and live their best lives. Still growing and developing, we know children’s brains are not yet fully formed, particularly in areas responsible for impulse control, reasoning, and understanding consequences.

And children who are victim-survivors of family violence, with disability, neurodiverse, have poor mental health and First Nations children, are significantly more likely to be respondents to intervention orders.

Our data analysis and the stories from our young clients and their families show that the intervention order system needs a rethink for children and young people.

Client experiences

Our research findings – and what needs to change

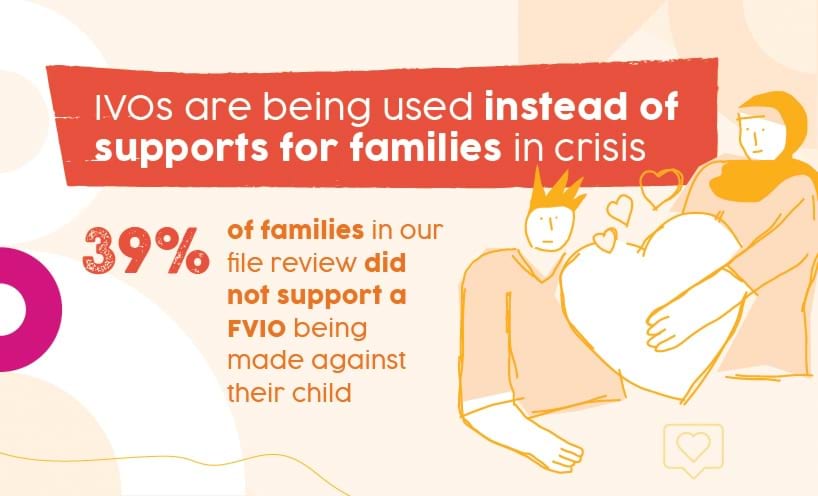

1. Intervention orders are being used instead of supports for families in crisis

Young children often do not understand legal orders like intervention orders. Applying adult legal frameworks to young children does not change their behaviour or improve safety. Our data shows intervention order applications are being made against children as young as 10. Victoria Legal Aid system data shows that 33 per cent of our child respondents to intervention orders were aged 10–14 years.

We recommend raising the minimum age for respondents to intervention orders to at least 14 and to ensure that intervention orders against children are used as a last resort.

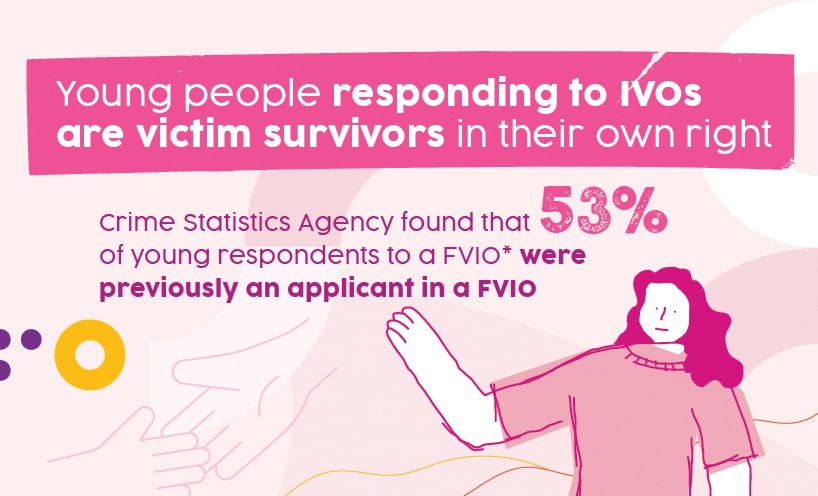

Many of our young clients responding to family violence intervention orders (FVIOs) are victim-survivors of family violence in their own right. Crime Statistics Agency data confirmed that over half of child respondents to FVIOs were previously applicants to FVIOs.

Our data showed that one in four young respondents were reported to have a disability, including a mental health issue. Almost half of the FVIO files we looked at arose in the context of a behavioural outburst linked to the young person’s disability. This was often in connection with parents removing access to their child’s phone or iPad or disconnecting the internet

'Our 15-year-old is not going to abide by it anyway...he’s a good kid, but if something like that happened again, he wouldn’t be thinking about the intervention order. He’d be thinking about his anger in that moment. What am I supposed to do then? I’m supposed to call the police and have him charged with a crime?'

Luke, father, FVIO

We recommend various changes to Victoria Police policy and practice, including alternative first responders for children experiencing mental health crises.

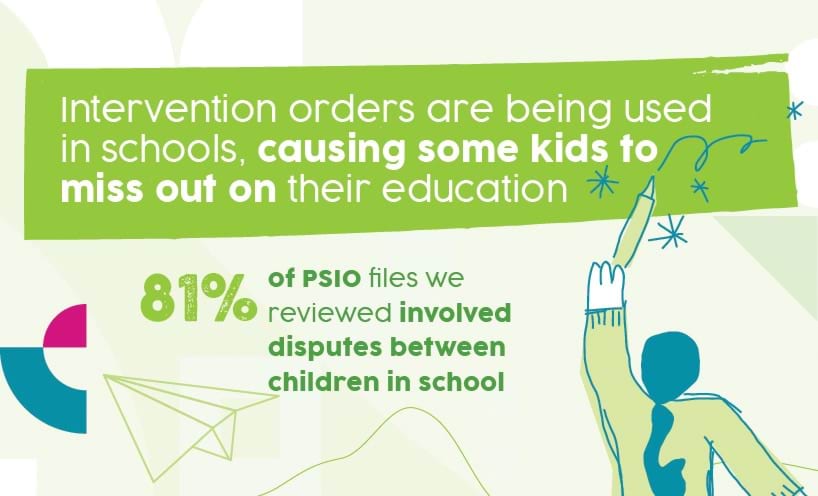

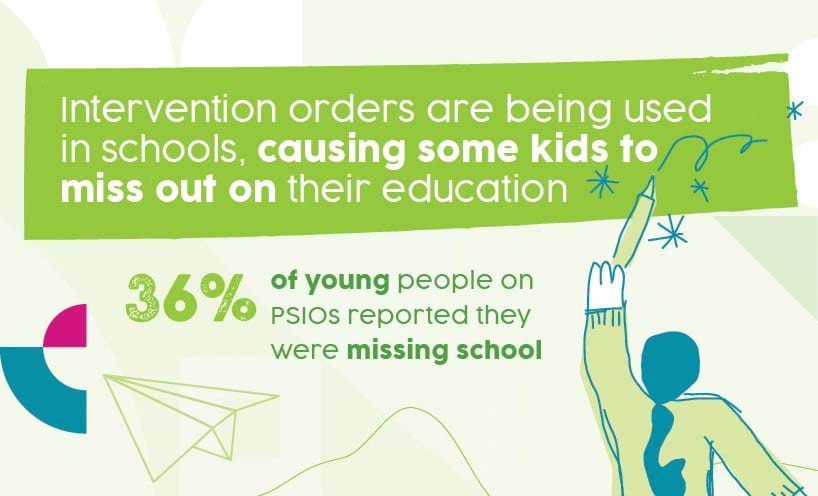

2. Intervention orders are increasingly arising in schools and can lead to school disengagement

For education to empower young people to reach their potential, schools must be safe and inclusive environments where every student feels supported.

This report contributes new evidence about how disputes related to schools, including verbal and physical fights or online incidents between classmates, are attracting a legal response. From our file review, we found the majority of PSIO applications against children related to school disputes between classmates.

‘It would have been better if the person let the teachers handle it.’

Isaac, 14

Our research shows the serious impacts intervention orders have on young people’s access to their education - an international human right. Our file review showed 36 per cent of young peoples’ schooling was disrupted by the PSIO. Disruptions included missing some school, changing schools or leaving school altogether.

Half of the young people whose schooling was disrupted by a PSIO were neurodivergent or had mental health issues.

‘School is supposed to be a place where kids can be safe and they’re not.’

Serena, mother

We recommend the Victorian Department of Education provide greater support to schools to resolve disputes and to further invest in programs to support children to stay in school.

3. The intervention order system is not helping children or their families

We all benefit when families, especially those caring for young people with complex needs, have access to joined-up support, including family violence support, disability and mental health care, supports to re-engage students in education, and youth services that de-escalate conflict and strengthen safety.

Families need early and coordinated support that helps them manage conflict safely. However, we heard from parents who had reached out to services and government agencies for help with their child’s behaviours that they could not get the support they needed.

Our review of Victoria Legal Aid files showed that 42% did not include evidence of the intervention order process linking the young person to a new or existing support service.

‘I felt hopeless. I didn’t want the charges, but the police went ahead just doing their own thing.’

Maggie, mother, FVIO

Using intervention orders to manage family conflicts adds pressure on families and increases the risk of criminalisation. Crime Statistics Agency analysis found that 17 per cent of children aged 10 to 17 were charged with a breach of the FVIO. In our file review we found nine out of the ten children charged with a breach of an intervention order had a disability.

We recommend the Victorian government invest in more prevention and early intervention for families.

4. Children are left out of court processes

When children’s voices are heard in court, decisions are better informed and lead to safer and fairer outcomes for families and communities. However, 70% of children in our file review with an interim order were not at court when the order was made. There is no requirement for children to be at court for intervention order hearings and orders can be made in their absence, although orders only come into effect if the young person has been given a copy. A common reason young people tell our lawyers why they were not present is because police told them they didn’t need to go to court.

‘I felt like I didn’t deserve it to be on me. I felt like it was kinda shit. It was like, just another add-on and it just didn’t feel right. It made me pretty anxious and pretty angry as well.’

Spencer, 15, PSIO

For disputes between children, mediation can have ongoing benefits such as understanding the root causes of the dispute and learning conflict resolution skills. However, our file review showed just two per cent of PSIOs were resolved through mediation in the Children’s Court.

'Maybe have a call with them first or with both in the courtroom… and give both of them a chance to tell their side of the story.'

Spencer, 15, PSIO

We recommend that more children should be diverted away from legal processes and into therapeutic support services to tackle their underlying needs.

We recommend that the Victorian government fund further research into the effectiveness of PSIOs against children.

Watch the launch of the report

Download the report

Contact

If you would like more information please contact Family Youth and Children’s Law Strategy Manager Alma Mistry at alma.mistry@vla.vic.gov.au

Updated